Knee Surgery & Rehabilitation

Instability of the kneecap – or the patella – is one of the most common reasons patients seek medical treatment at the Noyes Knee Institute. Normally, the patella glides smoothly and stays within what is called the trochlear groove as the knee flexes (bends) and extends (straightens). An unstable kneecap comes either completely or partially out of the groove as the knee bends.

The term “patellar instability’ may indicate either a dislocation, where the kneecap comes completely out of its normal position, or a subluxation, where the kneecap only partially moves out and then goes back into its normal position.

There are many potential causes of patellar instability, ranging from a traumatic injury to inherent problems with the patient’s anatomy that predisposes them to this problem.

E-Book Series Unstable Kneecap

Frequently Asked Questions

ACL Reconstruction What you need to know:

What are the common risk factors for patellar instability?

- Traumatic patellar dislocation injury

- Age less than 20

- Excessive weakness, tightness, or imbalance of the dynamic stabilizers

- Abnormally shaped trochlear groove

- Deficient medial patellofemoral ligament from a prior injury or congenital laxity

- Family history of patellar dislocation injuries

- Patellar dislocation opposite knee

In addition, there are other more rare conditions that may influence patellar stability:

- A rotational malalignment of the femur and tibia known as “miserable malalignment”

- A patella alta position (where an abnormally long patellar tendon affects the position of the patella)

- Problems from previous surgery, such as an overly extensive lateral release

What causes patellar instability?

In order to understand how and why the patella may become unstable, a general understanding of the basic anatomy and mechanics of the patellofemoral joint is required.

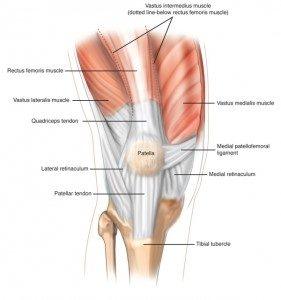

The patellofemoral joint is the area of the knee where the patella and femur meet. There are many structures that affect the function of the patellofemoral joint in terms of how the patella tracks and absorbs the forces of weight bearing. These structures are collectively referred to as the “extensor mechanism” and they propel the legs forward when you walk, run, or jump. An injury, deficiency, or anatomic abnormality of any of these structures may result in patellar instability.

- Quadriceps muscles (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius)

- Quadriceps tendon

- Patella

- Patellar tendon

- Medial retinaculum

- Lateral retinaculum

- Medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL)

- Tibial tubercle

What are the specific factors that influence patellar stability?

Patellar stability, defined as the condition in which the kneecap glides normally and stays within the trochlear groove as the knee flexes and extends, is influenced by several factors:

- Angle of Knee Flexion and Dynamic Stabilizers

A quadriceps (thigh) muscle contraction straightens the knee by pulling at the patella, which in turn pulls on the tibial tubercle, causing the knee to extend. As the knee flexes, the patella acts like a pulley, causing the kneecap to be pressed into the trochlear groove.

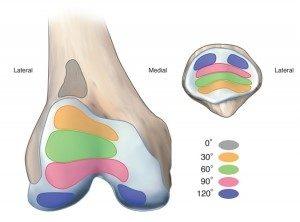

The patella is most unstable in the range of 0-30 degrees of knee flexion (0 degrees indicates that the leg is straight). The quadriceps muscles are relaxed at this angle and the patella is not seated in the trochlear groove. Thus, it can easily be moved either towards the right or left.

As the knee bends, patellar stability is normally increased due to the combined tensions of the quadriceps muscles and the patellar tendon that pull the patella into the trochlear groove. The vastus medialis oblique (VMO) muscle pulls the patella toward the inside (medial) of the knee joint. The MPFL acts as a check-rein to resist a patella dislocation toward the outside (lateral) portion of the knee joint. The vastus lateralis muscle tends to pull the patella toward the outside (lateral) aspect of the knee.

It is also important to understand the relationship between knee flexion and contact that occurs between the patella and trochlear groove. When the knee is full straight (0 degrees), there is very little contact between the undersurface of the patella and the trochlear groove. Then, from 0-90 degrees of knee flexion, increased contact occurs. At first, contact occurs between the inferior (distal) pole of the patella and the trochlea. Then, as flexion increases to about 45 degrees, the contact area moves toward the central portion of the patella. At 90 degrees of flexion, only the superior (top) region of the patella is in contact with the distal aspect of the trochlear groove. At approximately 120-135 degrees of flexion, only the most medial and lateral parts of the patella come into contact with the lateral and medial femoral condyles.

Forces on the patella rise to about 3 times body weight when climbing up stairs, 5 times body weight when descending stairs, 7 times body weight during running, and up to 20 times body weight during deep squatting. The quadriceps muscles absorb energy during walking and running.

An alteration caused by excessive weakness, tightness, or imbalances of the dynamic stabilizers may result in patellar maltracking or instability problems, and increase the forces on the kneecap that lead to eventual deterioration of the joint lining.

- The Shape of the Trochlear Groove and Lateral Femoral Condyle

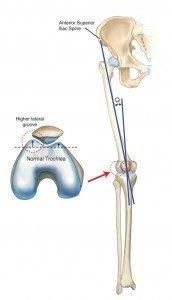

When looking at a leg from the front, the quadriceps muscles and tendon do not form a straight line. They point one way above the patella, and another way below the patella. The quadriceps angle (Q angle) is the angle formed by one line drawn from the pelvis anterior superior iliac spine to the middle of the patella, and a second line drawn from the middle of the patella to the tibial tubercle. The normal Q angle in men ranges from 8-14 degrees. In women, the normal Q angle ranges from 11-20 degrees.

Because of the Q angle, the patella has a tendency to be pulled toward the outside (lateral portion) of the knee when the quadriceps muscles contract (tighten). This is where the shape, height, and slope of the trochlear groove is important to help keep the patella in its proper position. Normally, the groove is higher on the outside (lateral side), which keeps the patella from sliding out of position as the knee bends and straightens.

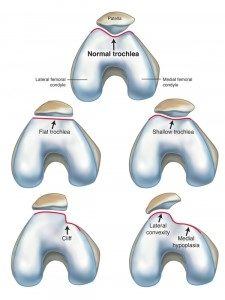

There are different shapes, or variations of the trochlear groove. There is what is considered a normal appearance (just shown in the illustration above) and 4 variations called shallow, flat, convex, and cliff. These 4 variations are associated with what is termed trochlear dysplasia, or an abnormal shape of this area of the knee. A shallow or dysplastic trochlear groove that develops in some people allows the patella to move too far side-to-side and may be a source of chronic patellar instability problems.

- The Medial Patellofemoral Ligament

The MPFL is a very important static stabilizer that helps prevent the patella from moving too far laterally out of the trochlear groove. Our understanding of the vital role this ligament plays in patellar stability is fairly recent (within the last 15 years or so). In knees with a large Q angle, the MPFL provides a balancing force that resists the increased lateral pull on the patella.

The MPFL is always damaged in patellar dislocation injuries, although the extent of the damage varies and does not require surgery initially. Over time, the amount of damage to this ligament may become more of a problem if patellar subluxation or dislocation episodes continue. A second ligament located on the medial side of the knee called the medial patellomeniscal ligament is another important stabilizer.

Some people have excessively tight static stabilizers, such as the medial or lateral retinaculum. Excessive looseness of these structures may also cause problems with patellar stability.

- The Hip Muscles

Researchers have recently emphasized the role of the hip muscles in patients with patellar pain and instability. Realize that the hip shares a common bone with the knee – the femur. At the hip joint, the femur connects with the acetabulum of the pelvis and acts as a “ball-and-socket” joint that moves in all directions. At the knee joint, the femur is tightly connected to the tibia through ligaments, tendons, and the joint capsule.

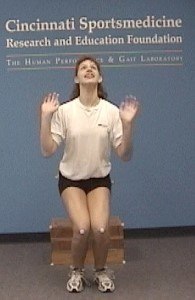

Weakness of the hip muscles (hip abductors and external rotators) may directly impact the knee joint by causing the femur to internally rotate and the knee to go into a knock-knee (valgus) position and the foot to turn outward (pronate), as shown in the photograph below.

A few studies have shown that patients with patellar pain and instability have weak hip muscles, but it is unclear if this problem was present before or as a result of the patellar pain.

What is extensor mechanism malalignment?

Extensor mechanism malalignment is a commonly used phrase by orthopaedic surgeons to describe patellar tracking or instability problems. The term indicates an abnormal relationship between the patella and trochlear groove, which may be due to problems with the static and/or dynamic stabilizers we just discussed.

Some problems associated with soft tissue and muscle weakness or tightness may be resolved with muscle strengthening and flexibility exercises, shoe inserts, anti-inflammatory medications, and restriction from high-impact activities that overload the knee joint. However, there are cases where some of the stabilizers are completely deficient and unable to function properly that require surgery.

What is "miserable malalignment"?

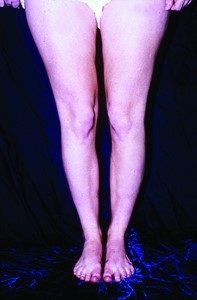

The term “miserable malalignment” was first introduced in the medical literature in 1979 by orthopaedic surgeon Dr. Stan James. This type of malalignment, which is inherited, is referred to as a rotational malalignment because the femur at the hip joint is rotating inward while the tibia is rotating outward. These problems become quite pronounced during weight bearing activities. There exist two abnormalities related to the bony alignment: femoral anteversion and external tibial torsion. Femoral anteversion produces an inward pointing, or “squinting”, patella, shown here:

Patients with this syndrome who have significant patellar pain and frequent dislocation or subluxation episodes may require an extensive operation known as a rotational osteotomy of the femur and tibia. Because this represents a very complex condition, we will not discuss this problem in detail here. It is important to understand that the orthopaedic surgeon must determine if this rotational malalignment is present because if it is, surgery at the knee joint is contraindicated. Instead, the rotation is corrected at the femur and tibia. If a surgeon suspects this problem may be present, a special diagnostic study (called a rotational magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) at the hip, knee, and ankle is obtained so that precise measurements may be made.

What happens after patellar dislocation injuries?

Patellar dislocations are categorized as either low-energy or high-energy injuries. In a low-energy injury, only a small amount of force is required to dislocate the patella, such as a sudden twisting injury in a knee with abnormally lax medial patellar ligaments and a dysplasic (flat) trochlea. On the other hand, a high-energy injury involves much greater force, such as that incurred by a direct blow to the patella during sports.

Nearly all patellar dislocations occur in the lateral direction, meaning the patella slides out of the groove toward the outside of the knee. The patella may return to the normal position on its own (called a spontaneous reduction), or the patient or a medical professional may have to relocate it back into place. This painful injury is often accompanied by swelling and loss of normal knee motion and requires a medical evaluation

Studies have shown that 50-80% of patients who sustain a high-energy patellar dislocation also suffer an osteochondral fracture, whereby the articular cartilage lining and bone on the undersurface of the patella or femoral condyle are torn and fractured. Osteochondral fractures may require surgery to remove the damaged joint fragments.

The MPFL is always damaged in dislocation injuries and nearly all patients sustain a bone bruise to the patella and lateral femoral condyle. These problems occur much less frequently in patients with low-energy injuries.

Fortunately, most patients who suffer first-time patellar dislocations do not require surgery. However, there are some instances where an operation is necessary soon after the injury. In all patients, appropriate orthopaedic management of the injury is required, including a comprehensive examination, x-rays, and often MRI to determine the extent of the damage to the knee. A course of protection, partial weight bearing with crutches, bracing, and physical therapy is required to restore normal knee and lower extremity function.

In the first few months following a patellar dislocation injury, patients may experience pain, fear, and problems with kneeling, squatting and all sports activities. One study found that 58% of patients had significant problems with strenuous activities 6 months after their injury. While many patients will not experience further patellar instability problems following appropriate management, studies have reported that 14-57% of adult patients and 36-71% of children and teenagers will suffer recurrent dislocation injuries. These patients are at risk for incurring further damage to the stabilizing ligaments and soft tissue structures that surround the patella

Studies have reported that > 90% of patients who suffer from recurrent patellar dislocations develop damage to the articular cartilage joint lining in the patellofemoral joint. Therefore, all efforts should be followed to prevent a recurrent dislocation and further damage to the knee joint. Surgery usually becomes necessary in these cases to restore normal patellar stability and knee function, which should be done before significant joint damage occurs.

What are patellar subluxation episodes and how are they different from dislocations?

Patellar subluxation refers to when the kneecap moves partially out of the trochlear groove during knee flexion and then goes back to its normal position. These episodes are less painful than dislocations, but may eventually cause problems if they occur frequently and are not treated effectively. This problem may happen suddenly without warning during sports or regular daily activities. It may be thought of as a temporary, partial dislocation of the kneecap. Patellar subluxation may happen due to malalignment (anatomical) problems we previously discussed, weak leg and hip muscles, or from damage to soft tissues from a previous patellar dislocation injury.

Recurrent patellar instability results in pain that may be felt under, around, or most commonly, in the front of the kneecap. Patients may experience knee giving-way or buckling (instability) during sports activities that involve twisting and turning, running on uneven surfaces, and even during daily activities such as squatting, kneeling, and going up and down stairs. These problems result in a decrease in physical activity due to lack of confidence in the knee joint.

Cases of patellar subluxation (without a history of a traumatic injury) need to be carefully evaluated to determine the causes of the problem which, in many patients, may be greatly helped with conservative treatment methods. Surgery is delayed to allow for muscle strengthening, balance training, and often a patellar support brace is used during sports. In some patients, the type of sport and/or the level of participation needs to be changed. For instance, sports that involve jumping, twisting, or turning activities may repeatedly aggravate the problem. If conservative methods fail to prevent recurrent subluxation episodes, surgery may become necessary to correct all anatomic abnormalities that exist.

This is why, in cases of patellar subluxation or recurrent dislocation, it is important for the physician to determine exactly what is causing the instability in order to treat the problem correctly. A diagnosis requires a thorough examination of the knee and entire lower limb that includes x-rays and a MRI. There frequently exists more than one source or cause of patellar instability that requires treatment. At the NKI, we spend a considerable amount of time and obtain all tests required to determine all of the factors that are causing your kneecap problems. Then, an accurate diagnosis will allow a treatment plan to be developed.

What are the exact diagnoses of patellar instability?

- Extensor mechanism malalignment

- Miserable malalignment syndrome

- Patella alta

- Patella infera

- Bipartite patella (patella with two pieces)

- Problems related to failed previous surgery, such as an excessive lateral retinacular release that causes medial patellar subluxation

- Genu valgum (knock-kneed)

- Genu varum (bowed leg)

- Genu recurvatum (hyperextended knee)

- Fat pad swelling (Hoffa’s disease)

- Articular cartilage damage in the patellofemoral joint

How are unstable kneecap problems treated?

Nearly all patients who come to the NKI for patellar instability undergo conservative treatment consisting of a comprehensive, supervised physical therapy program. They may be prescribed a knee brace or sleeve, shoe inserts or orthotics, a weight loss program, and appropriate medications if swelling is a problem. The good news is that many patients are greatly helped with this program and surgery is not necessary or can be avoided for a long period of time. Our rehabilitation team has decades of experience in treating all of the possible causes of patellar instability and often, the problems of muscle weakness and imbalance are resolved with a dedicated patient and therapist team approach. However, if the patient has rehabilitated to the best of the medical team’s ability and problems persist, surgery may become necessary.

When is surgery necessary?

The goals of surgery are to correct any malalignment issues, balance soft tissues, and reconstruct torn or deficient ligaments (especially the MPFL). Many different types of operations are available for extensor mechanism malalignment. This is where the physical examination and either CT or MRI determine important factors such as the Q angle, patellar translation (glide or movement) and tilt, lower limb rotational alignment (femoral anteversion and external tibial torsion), shape of the trochlear groove, the tibial tubercle-trochlear groove (TT-TG) distance, and patellar height (to diagnose a high riding patella [patella alta]; positive J sign). Some of the common operative procedures include:

- Lateral release

- Proximal realignment

- Proximal-distal realignment

- Reconstruction of the MPFL and proximal realignment

In addition, several types of operations may be done for patients who have significant damage to the knee joint lining (articular cartilage). The goals of treatment are to restore function and allow the patient to resume normal activities, depending on the damage that is present. Another goal is to prevent further damage because this may lead to the necessity of a joint replacement years later. The articular cartilage procedures done at the NKI include:

- Arthroscopic debridement, abrasion arthroplasty

- Osteochondral autograft transfer

- Autologous chondrocyte implantation

When the damage to the articular cartilage becomes severe and, over time, the normal amount of joint space is lost, a partial or total knee replacement may be required. Replacing just the patellofemoral joint is a valid treatment option, especially in patients 40-50 years of age (and sometimes younger) if other operations have failed to alleviate their kneecap pain and the medial and lateral compartments of the knee are not damaged. We have written an eBook, “Partial Knee Replacement: Everything You Need to Know to Make the Right Treatment Decision” which discusses the issues of replacing just a portion of the knee joint.

What is the postoperative rehabilitation program?

All patients at the NKI who undergo surgery meet with the physical therapy team before their operation and are educated regarding the postoperative rehabilitation process. We believe that preoperative counseling is necessary to ensure the patient understands what is required of them in order to have the best possible chance of achieving a successful outcome.

After surgery, all of our patients begin their rehabilitation within a day or two after the operation. It is vital for all patients to begin working on regaining the ability to bend and straighten their knee and strengthen their leg and hip muscles. Our approach greatly lessens the chance of a complication that may occur if excessive scar tissue forms around and within the knee joint or if a great deal of muscle strength is lost.

In cases where large operations are performed, the patient will need to work for several months to restore normal knee function. Most of the exercises are performed at home or in a health club, but the therapist will guide the progress of the entire program. Click here to see our rehabilitation program for proximal-distal realignment and MPFL reconstruction.